The first time I heard someone mention the word "god," my tweenage self was glued to the screen watching a boy band accept some award on a televised award show. This was in the days before I discovered punk rock (and the depth of my angst) and sat clutching the Claire's bracelets that were in the process of turning my wrists green. Each member of the group thanked god for their win and, from the kitchen where she stood at the sink doing dishes, my mother muttered something sarcastic about how silly it would be for their moms to get thanked first for the hours of driving back and forth to classes and sitting through all of their recitals. (This probably also came at the tail end of one of the many lessons I'd begged my mom to let me start and, a few hours later, begged her to let me quit.) That night I sat in my room writing fake award acceptance speeches for the songwriting successes that I predicted I would have, especially once I married my favorite boy band member (Brad from LFO, I'm looking at you, buddy) who was madly in love with me. This was also the time I asked my mom about god and religion with a confusion that stemmed from something so unimportant in our family somehow being so important to so many. In my fake acceptance speech I still thanked my future husband Brad from LFO over my mom (who I added in as an afterthought -- sorry, mom) but I didn't see where god fit in. Even the woman who developed photos at Walgreens earned herself a mention, but god? I mean, what did that even mean? My mom calmly explained that children cannot simply be whatever religion their parents are by force. Religion, she declared, is something you must be educated on before you can have an opinion. It isn't something passed down, but something that must be chosen carefully once someone is educated enough to make that decision.

That's basically the story about how my Jewish mother and Catholic father raised two atheists.

By college, I'd vacated the cushy Jewish suburbs and found myself smack dab in a Bible belt where people felt that you couldn't be good without god. People cared so much about religion that they stood on street corners with big signs promising eternal damnation and chased girls trying to pick up their birth control pills outside of Planned Parenthood. I took religion classes in college to educate myself and defend my godlessness against those who glued wooden crosses to my car in some backwards attempt to convert me (my marriage equality bumper sticker gave me away, apparently). The years passed by and I got married and settled our family back into a place where diversity runs rampant and you can buy your birth control pills in peace. But there's still hatred in the world. Once in a while, a synagogue is desecrated. Once in a while, a SCOTUS ruling brings the people to our street corners with their big, damnation-promising signs. Once in a while, I find myself reading promises on the Internet about how blood-thirsty atheists are shooting up schools and eating babies for lunch, basking in the depths of their evil simply because they reject the idea of god. Although diluted these days, society still leans towards god being good and godlessness being bad.

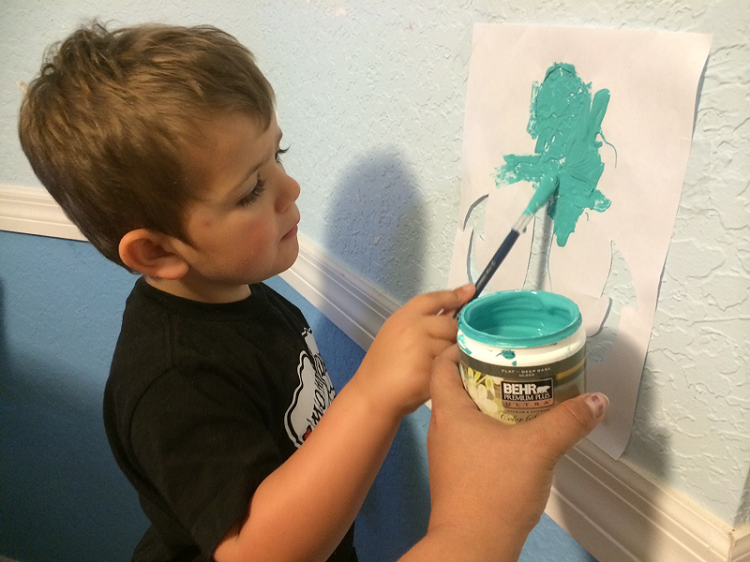

It's these times that I remember what it was like growing up under my mother's care. We were raised to do good, we were raised to be kind. We were taught that no child was bad. "You know," my mother would say, gesturing towards the homeless person standing in the median, "they were once someone's baby. Someone handed that baby all bundled up to their mother. Someone loved them so much. That's someone's baby." And we always gave something -- a dollar, some water, kindness -- to someone's baby. When I brought home friends with empty bellies and broken hearts, friends who came from shattered homes and dim futures, my mother fed them. She let them find a safe space in our home. She watched their bands play when their parents didn't show. I'm a parent now, and my child knows my arms are his safe space. He knows his ideas are never wrong or stupid. He knows that someone's hair color, skin color, tattoos, language spoken, religion, economic status -- these aren't things that define a person. He will grow to know that we don't give up on people no matter their appearance, their past mistakes, their addictions or failures or successes, because love and kindness are magic on Earth.

Kindness.

My son, too, will grow up saturated in kindness -- and not because if he is unkind he will be punished eternally, but because kindness, love and being a good person is the way everyone should be. You know, on principle. Because everyone deserves an equal shot at happiness and everyone deserves to be loved.

---

Sometimes, my godlessness feels like a secret. A dirty one. The kind of secret you can only tell your closest friends who have known you so long that they have no choice but to like you forever at this point. The thing is, it's not a secret and it's not a point of shame, but a point of pride. For every person who tells me what a great mother I am, what a great person I am, what a great friend I am, how inspirational my family is -- it is because they see me and feel that way still. They see me for who I am, the outspoken mama who isn't afraid to be a voice for someone who has lost theirs, and they feel that way because you don't need god to be a good person. Because even though Brad from LFO grew up to be an anti-choice evangelical, antagonistic pain in the ass (it wouldn't have worked out anyway, Brad, sorry to break it to you, dude), I'm going to opt to be the friend who holds your hand when you walk into Planned Parenthood to terminate an unwanted pregnancy and I'm still going to hold your hand when you carry a fetal anomaly pregnancy to term. I'm going to give the homeless what I can and teach my son the power of love, the power of kindness and the power of holding others up. I'm going to keep living my life, with my clear conscience, as I always have because the world needs more kindness. It needs more warmth. It needs more goodness and gentleness and friendship and acceptance. That's my goal, as it always has been. More love. More Kumbaya.

You see, my daughter isn't in heaven. I've had to explain this a lot lately, an automated response to people who blurt out these painful statements disguised as comfort based on beliefs that we don't hold. She's not in heaven, she's an in urn on the mantle. I'm looking at her photograph as I write this, her tiny urn to the left of it, silver with blue teddy bears etched on the sides. She's here with me. I don't believe in heaven. I don't believe I will see her again, or ever see her alive for that matter, and that is why her short live matters so. If you believe in heaven, I will hold your hand as you mourn the life of your loved one and I won't tell you where I believe your loved one is, because it's irrelevant to your comfort. Oftentimes, I find myself in a disagreement with others over who is right and who is wrong when it comes to my daughter. "But she is in heaven, she is." "Please, don't do this. Don't say that. She isn't in heaven." "Yes, she is, whether you like it or not, she is." "Stop." "No, because she is." And then I am supposed to nod and thank someone for crushing my broken mama heart into pieces tinier than I already believed it to be, because they're making me feel better even though they're not and then I feel it: the anger. I don't want to feel the anger anymore. I want to feel the impact that Wylie's life made on my own, and on our family, and raise up her memory with pride and kindness and strength and to let her legacy stitch together a blanket that brings more warmth to this world. Kindness has always been the backbone of our family and Wylie's life and legacy are no exception. Kindness first, love always. With or without god.

...And with Brad from LFO.

Because let's face it, you never forget your first love.